Land Art Project Planner

Land Art Project Planner

Recommended Action

Your project has a moderate environmental impact. Consider these steps:

- Use only locally sourced, biodegradable materials

- Limit the footprint to under 100 sq meters

- Implement a comprehensive restoration plan

- Work with an ecologist to monitor effects

Your Land Art Project Checklist

- Site selection completed

- Materials identified and sourced

- Permits secured

- Documentation plan created

- Environmental impact assessed

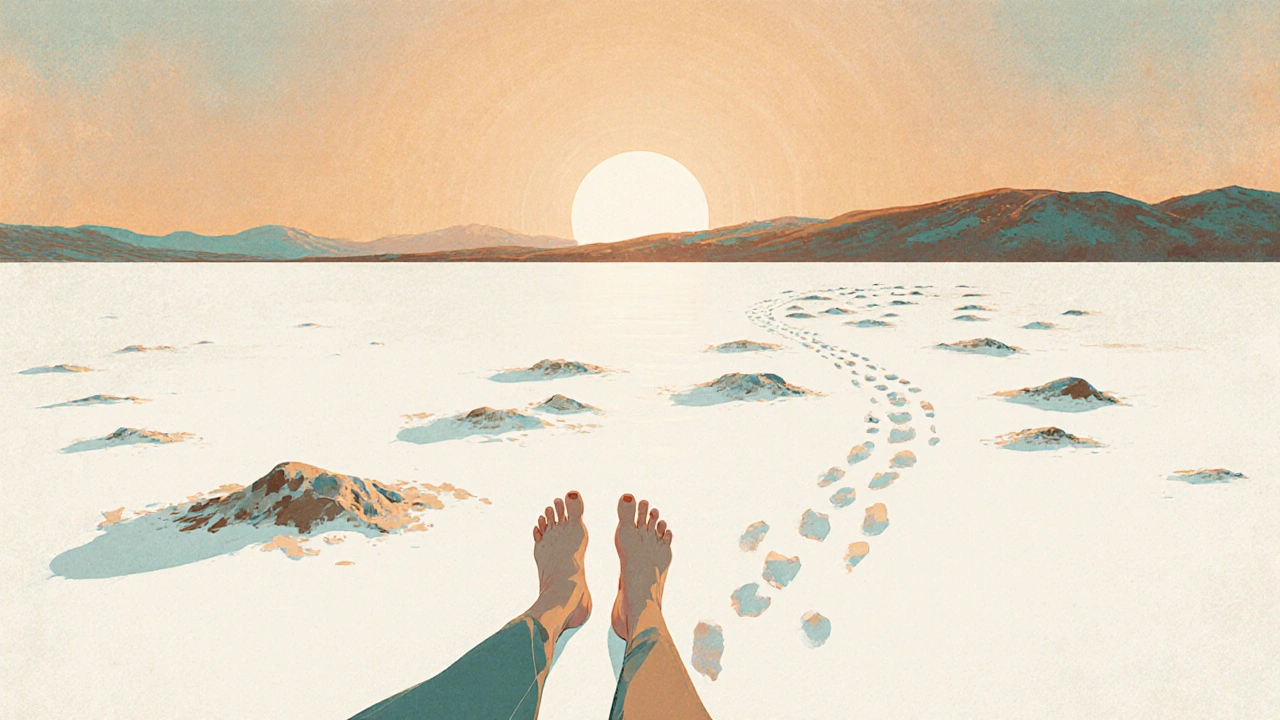

When nature itself turns into a gallery, the line between creator and landscape blurs. Land Art is a movement that treats the earth’s surface as both medium and message, letting soil, stone, and light speak in place of paint and canvas. This article walks you through the origins, iconic works, practical steps for creating your own piece, and the ecological debates that keep the conversation alive.

Key Takeaways

- Land Art emerged in the late 1960s as a reaction against gallery‑bound art.

- Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty and Michael Heizer’s Double Negative are benchmark works.

- Modern practitioners like Andy Goldsworthy blend art with deep ecological awareness.

- Permits, site access, and durability are crucial practical concerns.

- Understanding the difference between land art, environmental installations, and street art helps set realistic expectations.

What Exactly Is Land Art?

At its core, land art is site‑specific work that reshapes the natural environment to convey ideas about time, decay, and human impact. The art is not meant to be moved; it lives, erodes, and evolves with weather, wildlife, and the seasons. Unlike sculpture that sits in a museum, land art invites viewers to experience it in situ, often hiking miles to reach the piece.

The Historical Roots and Trailblazing Pioneers

While ancient cultures carved petroglyphs and earth mounds, the contemporary movement coalesced in the late 1960s in the United States. Artists sought to escape the commercial gallery system, using vast, remote landscapes as their studios.

Robert Smithson was a leading figure who coined the term "Land Art" in a 1968 essay, arguing that the medium should be unlimited and permanent. His most famous work, Spiral Jetty, consists of a 1,500‑foot coil of basalt and earth jutting into Utah’s Great Salt Lake. The piece appears and disappears with water levels, embodying the idea that art can be as fleeting as the environment itself.

Michael Heizer pushed the scale even further, excavating massive negative spaces in the Nevada desert. Double Negative involves two huge trenches cut into the basalt, each 30 feet wide and 70 feet deep. The voids become the artwork, challenging viewers to contemplate absence as a form of presence.

Another early pioneer, Walter De Maria created The Lightning Field, a grid of steel rods that attract natural lightning in New Mexico. De Maria’s work emphasizes the temporal, inviting visitors to spend hours watching the sky and considering the forces that shape our planet.

Iconic Works and Their Stories

Spiral Jetty (1970) - Constructed from local basalt, mud, and salt crystals, the spiral follows the lake’s shoreline. Salt crusts give it a shimmering quality, and when water recedes the artwork reveals a stark, white interior.

The Lightning Field (1977) - Twenty‑four stainless‑steel poles, each eight feet tall, are set in a precise 1,250‑by‑1,000‑foot rectangle. The site’s remoteness, combined with a strict visitor schedule, turns the experience into a ritual of patience and anticipation.

Double Negative (1970) - By removing earth rather than adding it, Heizer created a dialogue about what counts as “creation.” The work’s scale forces viewers to reckon with the desert’s own grandeur.

These pieces share three traits: massive scale, reliance on natural processes, and a location that is integral to meaning.

Materials, Techniques, and Ecological Considerations

Typical materials include earth, rocks, sand, wood, and industrial elements like steel or concrete. The choice often reflects the artist’s intent:

- Earth and stone - Emphasize permanence and integration with the landscape.

- Steel or aluminum - Highlight industrial contrast and can be treated to rust or gleam.

- Organic matter (branches, leaves) - Used by contemporary artists for temporary, biodegradable installations.

Environmental impact is a major conversation. Modern artists work closely with ecologists to ensure that interventions do not disrupt habitats. Permits from land management agencies, careful site surveys, and post‑project remediation plans are now standard practice.

Contemporary Voices: From Goldsworthy to Global Communities

Andy Goldsworthy is a British sculptor known for creating fleeting, site‑specific pieces using natural materials like leaves, ice, and stone. His process is meditative; he builds, photographs, and then lets the work dissolve. Goldsworthy’s works foreground the transience that early land artists only hinted at.

Across the globe, Indigenous communities are reclaiming land‑based art as a form of cultural expression, intertwining storytelling, stewardship, and contemporary aesthetics. Projects in Australia’s outback, for example, use native grasses and sand to map tribal histories onto the terrain.

How to Create Your Own Land Art Piece - A Practical Guide

- Define the concept. Ask yourself: What message about the environment do you want to convey? Is it a commentary on climate change, a celebration of a specific ecosystem, or an abstract interaction with space?

- Scout the site. Look for public lands with minimal bureaucratic hurdles, or collaborate with private owners. Record GPS coordinates, topography, and seasonal weather patterns.

- Secure permits. Contact local councils, park services, or heritage bodies. Provide detailed plans, environmental impact assessments, and a restoration strategy.

- Gather materials. Use locally sourced earth, stone, or reclaimed industrial components. The more the material originates from the site, the stronger the ecological narrative.

- Construct. Follow safety protocols, especially when excavating. Document each step with photos and notes-these become part of the artwork’s story.

- Engage the audience. Offer guided walks, QR codes linking to an online narrative, or silent observation periods to let the environment speak.

- Plan for change. Accept that weather will erode, grow over, or even erase the work. Decide whether you’ll maintain, let it decay, or re‑intervene after a set period.

Checklist for a sustainable project:

- Environmental impact assessment completed.

- All materials are non‑toxic and locally sourced.

- Clear agreement on post‑project site restoration.

- Documentation plan (photos, video, written narrative).

Land Art vs. Environmental Installation vs. Street Art - Quick Comparison

| Aspect | Land Art | Environmental Installation | Street Art |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Scale | Landscape‑wide, often miles | Medium to large, can be indoor or outdoor | Human‑scale, wall or pavement |

| Primary Medium | Earth, stone, water, natural processes | Mixed media, often incorporates technology | Paint, spray, stencil, chalk |

| Location Specificity | Integral to the site’s geography | Site matters but can be relocated | Often urban, can be moved or removed |

| Temporal Intent | Designed to evolve, decay, or persist indefinitely | Variable - can be temporary or permanent | Usually temporary, subject to removal |

| Typical Audience | Travelers, art scholars, nature enthusiasts | Gallery visitors, environmental activists | Passersby, local community |

Common Misconceptions and Pitfalls

Many people think land art is just “big rocks arranged in the desert.” In reality, it is a thoughtful dialogue with the environment. Overlooking permits can lead to legal trouble, and ignoring local ecology can cause irreversible damage. Artists also sometimes underestimate the cost of logistics-transporting heavy materials to remote sites can be expensive.

Preservation is another challenge. While some works, like Spiral Jetty, have been stabilized by conservators, others are intentionally left to fade. Understanding the artist’s intention regarding longevity helps avoid misguided restoration attempts.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is land art considered vandalism?

When done with permission and ecological care, land art is a recognized artistic practice, not vandalism. Unauthorized alterations of protected lands can be illegal, so securing permits is essential.

Can I create a land art piece on public parkland?

Many parks require a formal application, an environmental impact statement, and sometimes a fee. Contact the park’s management office early in the planning stage.

How long do typical land art works last?

Durability varies. Stone and earth pieces can endure for centuries, while organic installations may last days or weeks. The artist’s intention usually guides the expected lifespan.

Do I need an art degree to practice land art?

No formal degree is required, but knowledge of geology, ecology, and basic engineering helps. Many artists learn through mentorships and field workshops.

What are the biggest legal hurdles?

Land ownership, protected habitats, and cultural heritage sites can impose strict regulations. Always verify land titles and consult local authorities before commencing.

Land art invites us to see the planet not just as a backdrop, but as an active collaborator. Whether you’re an aspiring creator, a curious traveler, or a cultural historian, understanding its history, ethics, and practicalities opens a new way to listen to Earth’s own voice.