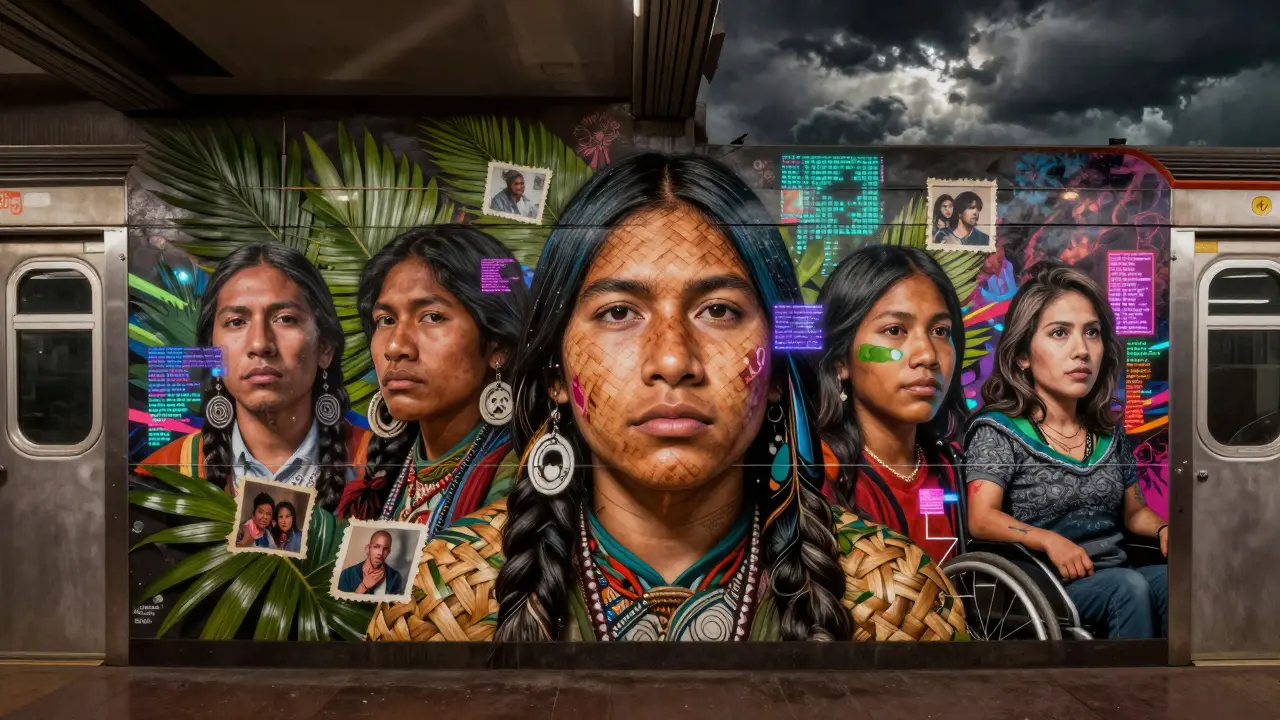

Look around you. The murals on the subway walls, the digital installations in galleries, the protest banners held up at rallies - these aren’t just decorations. They’re mirrors. Contemporary art doesn’t just hang on walls; it reflects who we are, who we’re becoming, and who we’re afraid of becoming. It’s not about pretty pictures anymore. It’s about questions. About race, gender, technology, climate, and the quiet loneliness of scrolling through a feed that never feels like home.

Identity Isn’t Fixed - Neither Is Art

For decades, art was seen as something timeless, made by geniuses, meant to be admired from a distance. Contemporary art throws that out the window. It’s messy. It’s personal. It’s often made by people who were never invited into the old art world - Indigenous artists, queer creators, migrants, disabled makers. Their work doesn’t pretend to be universal. It says: this is my truth. And if you don’t understand it, maybe you need to listen.

In 2023, the Venice Biennale featured a piece by a Tongan-Australian artist that used woven pandanus leaves, old family photos, and audio recordings of her grandmother speaking in a language no longer taught in schools. It wasn’t about technique. It was about survival. About memory that refuses to be erased. That’s contemporary art now - not about what’s beautiful, but what’s urgent.

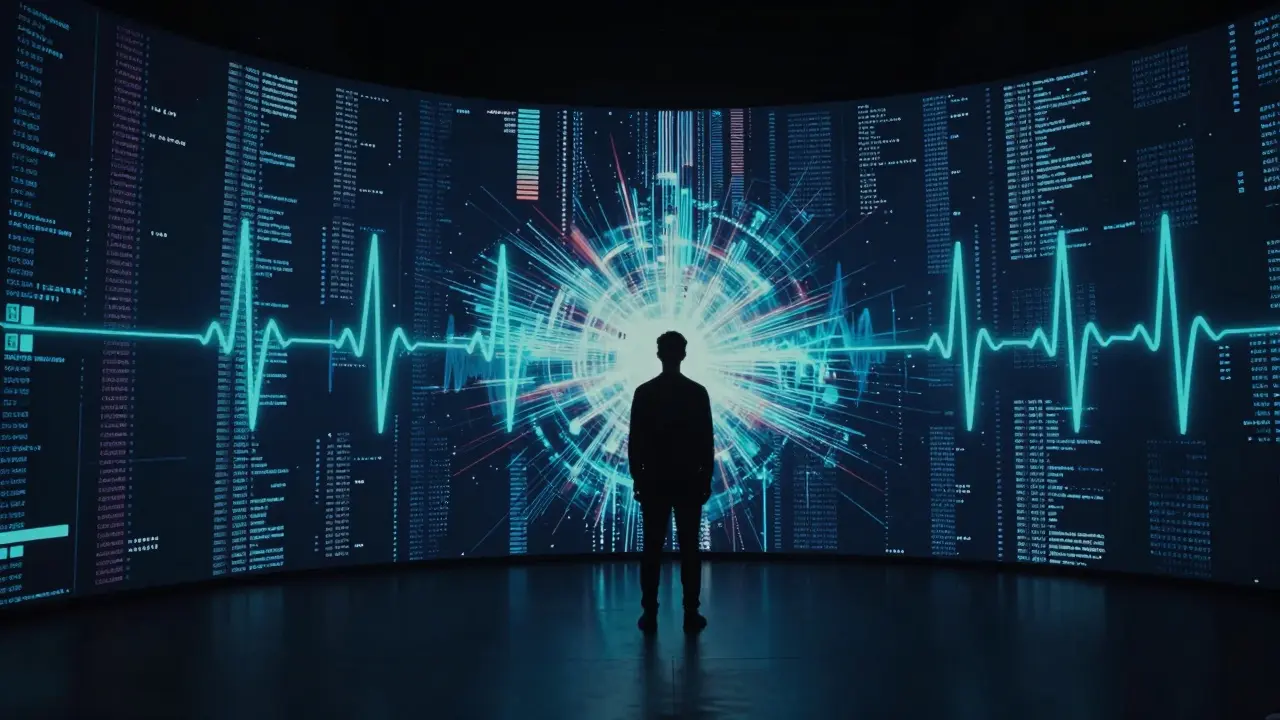

Technology Didn’t Just Change How Art Is Made - It Changed What It Means

Think about how you experience art today. You don’t just walk into a gallery. You scroll past a NFT on Instagram. You watch a video of an AI-generated portrait that sold for $432,500. You play a game where the characters are protest symbols from 2020. Art isn’t confined to canvas anymore. It lives in code, in algorithms, in TikTok filters that let you become someone else for 15 seconds.

Artists like Refik Anadol use real-time data - air quality, social media trends, traffic patterns - to create immersive installations that change every minute. His work isn’t a static object. It’s a living pulse of the city. And that’s the point. Our identity isn’t fixed either. We’re not just one person. We’re the version of ourselves we show on LinkedIn, the one we are with our family, the one we hide from strangers. Contemporary art captures that fragmentation.

Who Gets to Be Seen?

For years, the art world told us who mattered. White men. European traditions. Classical ideals. Today, museums are finally starting to listen. Not because they got nice. Because people demanded it.

Look at the rise of artists like Kehinde Wiley, whose portraits of Black men in heroic poses reframe centuries of Western art. Or the work of Tracey Emin, who turned her own trauma into neon signs that say things like “I Felt You.” These aren’t just artworks. They’re acts of reclamation. They say: I am here. My body, my pain, my history - it counts.

In Australia, artists like Brook Andrew and Yhonnie Scarce use colonial history as raw material. Scarce’s glass yams, delicate and shattered, represent the forced removal of Aboriginal children. They don’t shout. They whisper. And that’s what makes them powerful. Contemporary art doesn’t need to be loud to be heard. Sometimes, silence speaks louder than any protest.

Climate and the Body as a Political Canvas

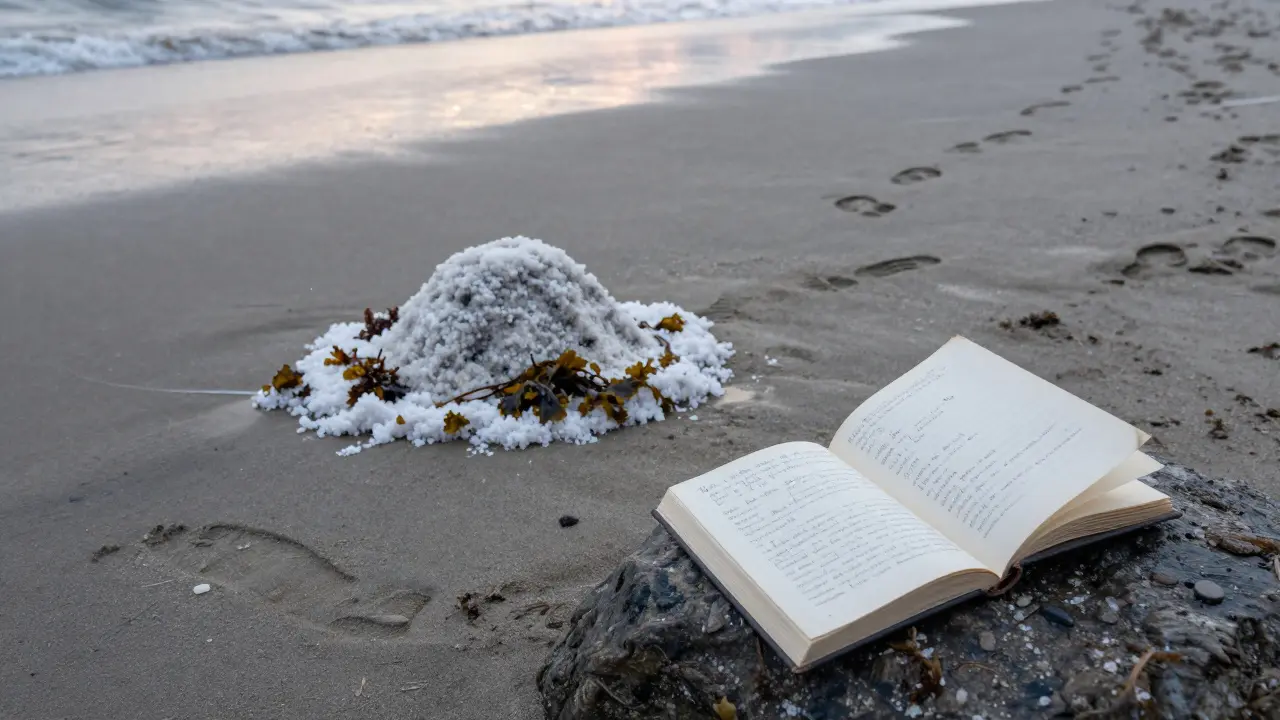

Climate change isn’t just a news headline. It’s in the way artists now work. They use recycled plastic. They grow art from fungi. They make sculptures from ocean debris. The material itself is part of the message.

In 2024, a collective in Perth buried a sculpture made of salt and seaweed in the dunes near Rottnest Island. It was meant to dissolve with the tide. No one was supposed to keep it. No one was supposed to photograph it. It was a ritual - a way of saying: we are part of the earth, not above it. That’s a radical shift from the old idea of art as something to own, to sell, to collect.

And then there’s the body. Trans and non-binary artists are using their own skin, hormones, scars, and surgeries as mediums. Their art isn’t symbolic. It’s literal. It says: this is me. Not a metaphor. Not a concept. This flesh. This breath. This identity. And it’s not up for debate.

Art That Doesn’t Want to Be Sold

Most art in museums is bought, sold, and displayed like luxury goods. But a growing number of artists are rejecting that. They make work that can’t be owned. Pop-up performances. Community murals. Interactive apps. Temporary installations that vanish after a week.

In 2025, a group in Berlin created a public library made of books written by refugees - each one handwritten, each one only available to read on-site. No copies. No digital scans. You had to be there. To sit. To listen. To feel the weight of someone else’s story. That’s not commerce. That’s communion.

This shift matters because identity isn’t something you buy. It’s something you live. And art that tries to capture it can’t be packaged. It has to be experienced. Right now. In real time. With real people.

Why This Matters for You

You might not think you ‘get’ contemporary art. Maybe you’ve walked past a weird sculpture and rolled your eyes. But here’s the thing - you don’t have to ‘get’ it. You just have to be willing to sit with it. To ask: why did this person make this? What are they trying to say that no one else is saying?

Contemporary art doesn’t give you answers. It gives you questions. And in a world where algorithms decide what you see, where politicians try to control what’s taught, where identity is policed on social media - having space for messy, complicated, uncomfortable truths is more important than ever.

That mural of a woman holding a child while wearing a gas mask? It’s not just about climate. It’s about motherhood in a collapsing world. That video of a dancer moving in slow motion while surrounded by scrolling headlines? It’s about how we’re drowning in information but starved for meaning.

Art doesn’t fix the world. But it shows us what’s broken. And sometimes, that’s the first step to changing it.

What makes art ‘contemporary’?

Contemporary art is made by living artists, usually after 1970, and reflects current social, political, and cultural issues. It’s not defined by style or medium - a painting, a video, a performance, or even a tweet can be contemporary art. What matters is that it engages with the world as it is now, not as it was.

Can art really change how people see identity?

Yes. Art doesn’t change minds with facts - it changes them with feeling. A photograph of a transgender teen holding their first ID card, a sculpture made from refugee clothing, a poem read aloud in a language once banned - these don’t argue. They invite you to step into someone else’s skin. That’s how empathy grows. And empathy is the foundation of social change.

Why is contemporary art so expensive if it’s about rejecting capitalism?

It’s a contradiction. The art world still runs on money. A painting by a Black female artist might sell for $2 million while she struggles to pay rent. That tension is part of the story. Some artists use that irony intentionally - making work that critiques the market while still participating in it. Others refuse to sell at all. The conflict isn’t a flaw - it’s the point.

Do I need to know art history to understand contemporary art?

No. You don’t need to know who Picasso was to feel the weight of a mural showing a child holding a sign that says ‘I’m not your future.’ Contemporary art often speaks in direct, emotional language. You don’t need a degree to feel something. You just need to be open to being unsettled.

Is contemporary art just random stuff people call art?

Some of it is. But most of what lasts isn’t random. It’s carefully chosen, deeply researched, and emotionally honest. A pile of bricks might look like nonsense - until you learn it’s made from soil taken from a site where Indigenous graves were disturbed. Then it’s not a pile. It’s a memorial. Context turns objects into meaning.