Cubism didn’t just change how art looked-it changed how we see the world. Before Cubism, paintings tried to trick your eyes into believing a flat canvas was a window into real space. Artists used perspective, shading, and careful lighting to make a still life feel three-dimensional. But in 1907, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque threw that rulebook out the window. They didn’t want to copy reality. They wanted to break it apart-and rebuild it from the inside out.

What Was Cubism Really About?

Cubism wasn’t a style. It was a revolution in perception. Instead of showing an object from one fixed viewpoint-like a photograph-Cubist artists showed multiple angles at once. A face might have a nose seen from the front and an eye from the side. A guitar might be sliced open to reveal its strings from above and its body from below. The goal wasn’t confusion. It was truth. They believed that to truly understand something, you had to see it from every angle, all at once.

This wasn’t abstract fantasy. It came from real observation. Picasso studied African masks, Iberian sculpture, and even the way people moved in crowded streets. He noticed how your brain pieces together a person’s face from memory, not just from what you see in a single glance. Cubism was the visual version of that mental process.

The Birth of Analytic Cubism

Between 1908 and 1912, Picasso and Braque developed what’s now called Analytic Cubism. Their paintings were mostly in shades of gray, brown, and ochre. Why? Because color distracted from form. They stripped away everything nonessential: soft edges, shadows, even clear outlines. What remained were fractured planes-sharp, angular, overlapping like broken glass.

Take Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). It’s often called the first Cubist painting. The women’s faces look like they’ve been smashed and reassembled. Their eyes aren’t aligned. Their noses are sharp angles. Their bodies seem to twist in impossible ways. Critics called it ugly. But it was honest. It showed how we perceive people-not as perfect, smooth surfaces, but as shifting, complex presences.

Braque’s House at L’Estaque (1908) did the same to architecture. A house wasn’t a building with a roof and windows. It was a stack of geometric shapes-triangles for roofs, rectangles for walls, cubes for chimneys-all viewed from different directions. The landscape behind it didn’t recede into distance. It collided with the house, as if space itself had been folded.

Why Perspective Was the Problem

For centuries, Renaissance artists had used linear perspective to create depth. One vanishing point. Parallel lines converging. A horizon line. It worked beautifully for landscapes and portraits. But it had a flaw: it froze time. It showed one moment, one angle, one fixed truth.

Cubists rejected that. They lived in a world of trains, telegraphs, and moving pictures. People traveled faster. Information moved quicker. Einstein was about to rewrite physics with relativity. Cubism mirrored that. It wasn’t about how things looked. It was about how they existed in time and space.

Think of walking around a chair. You don’t see it all at once. But your brain remembers the back, the legs, the seat. Cubist painters made that memory visible. They painted the chair as you know it, not as you see it in a single glance.

Synthetic Cubism: Building from the Ground Up

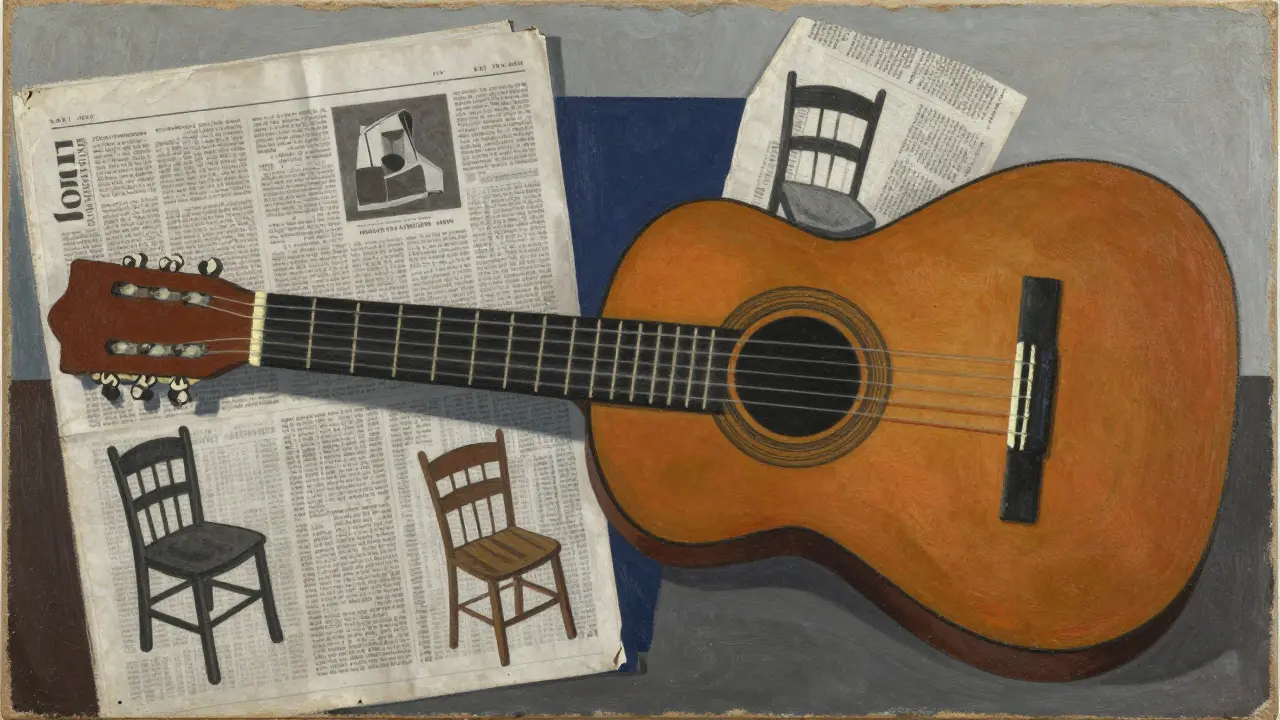

By 1912, Cubism evolved again. Synthetic Cubism didn’t break things apart-it built them up. Artists started gluing real objects onto canvas: newspaper, wallpaper, fabric, rope. Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning (1912) used oil paint and a piece of oilcloth printed with a chair pattern. It wasn’t a painting of a chair. It was a chair made of art.

This was radical. It blurred the line between art and life. Was the newspaper part of the scene? Or was it the artwork itself? You couldn’t tell. And that was the point. Reality wasn’t something you captured on canvas. It was something you constructed.

Letters, numbers, and text appeared in these works. A word like “JOU” (from the French “journal”) might be painted next to a guitar. It wasn’t decoration. It was a clue. It told you: this isn’t just a painting. It’s a moment. A memory. A collage of experiences.

Who Else Was Involved?

Picasso and Braque were the pioneers, but others followed. Juan Gris turned Synthetic Cubism into something more structured, almost architectural. His The Sunblind (1914) used precise geometry and bold color to create order from chaos.

Fernand Léger brought machines into Cubism. His figures looked like they were made of pistons and gears. In Nudes in the Forest (1911), bodies blend with trees and cylinders. It wasn’t about emotion. It was about rhythm, motion, the mechanical pulse of modern life.

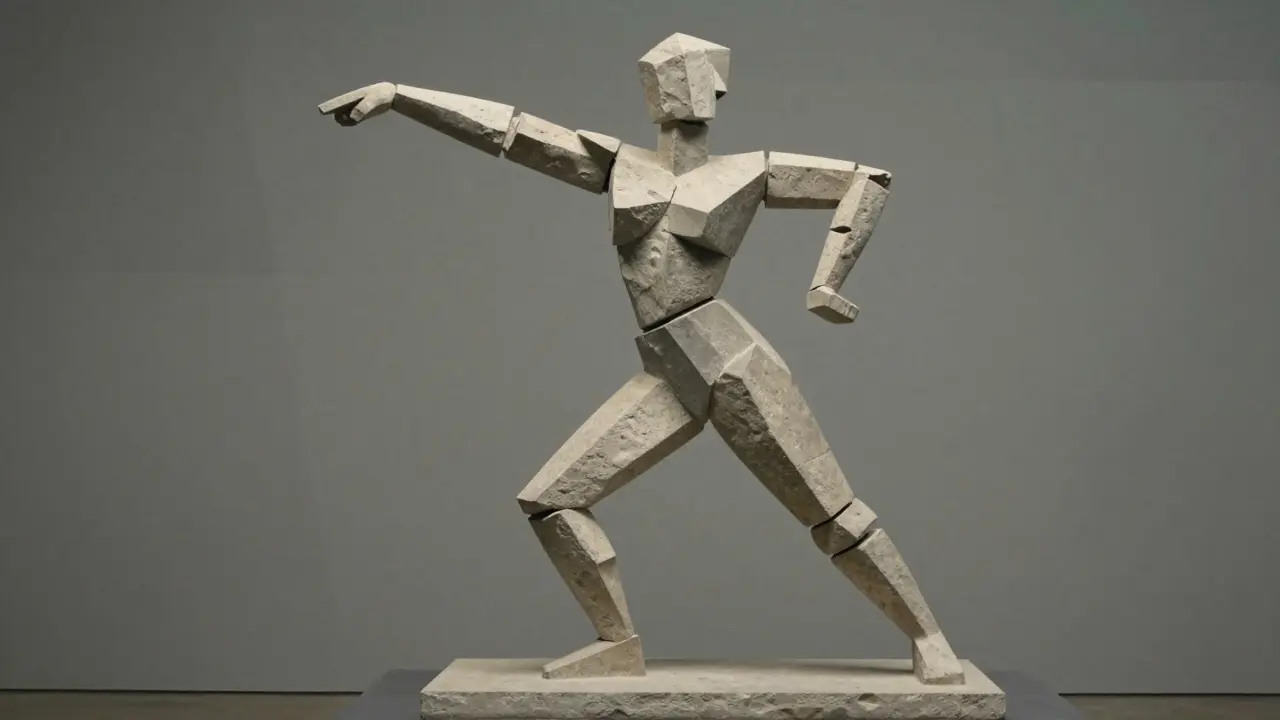

Even sculptors got involved. Jacques Lipchitz carved figures as if they were made of stacked cubes. His The Dancer (1915) doesn’t look like a person-it looks like a person’s energy frozen in space.

Why It Still Matters

Cubism didn’t just influence painting. It changed design, architecture, film, and even advertising. The angular shapes of Art Deco? That’s Cubism. The fragmented editing in Soviet films? That’s Cubism. The way modern logos use overlapping shapes? That’s Cubism.

Today, when you see a smartphone app with layered icons or a magazine cover with a face split into angles, you’re seeing Cubism’s legacy. It taught us that truth isn’t in a single view. It’s in the accumulation of perspectives.

Before Cubism, art was about imitation. After Cubism, art became about understanding. You don’t need to paint like a camera. You need to paint like a mind.

How to Recognize Cubist Art

- Objects are broken into geometric shapes-cubes, cones, cylinders

- Multiple viewpoints are shown at once (front, side, top)

- Shadows and light are flattened or ignored

- Color is often muted (early Cubism) or bold and flat (later Cubism)

- Real materials like newspaper or fabric are glued onto the surface

- There’s no single focal point; your eye jumps around the canvas

Common Misconceptions

Many think Cubism is just “weird” or “confusing.” But it’s not random. Every angle, every fragment, was intentional. Picasso spent years studying anatomy, perspective, and light before he broke them.

Others assume it was only about Picasso. But Braque was just as important. They worked side by side for five years, often painting the same subjects and exchanging ideas daily. Their partnership was the engine of Cubism.

And no, Cubism wasn’t a rejection of beauty. It was a redefinition. Beauty wasn’t in smooth curves anymore. It was in tension, in collision, in the way fragments come together to form a deeper truth.

What came before Cubism?

Before Cubism, European art was dominated by Realism and Impressionism. Realism aimed to copy nature exactly-detailed faces, accurate shadows, deep perspective. Impressionism broke that by capturing light and movement, but still kept a single viewpoint. Cézanne, who painted mountains and apples with simplified shapes, was the bridge. He said, "Treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone." Picasso and Braque took that idea and exploded it.

Why did Cubism use so many grays and browns?

In Analytic Cubism, artists avoided color to focus on form. Color draws attention to surface, but they wanted viewers to see structure. Gray, ochre, and brown were neutral tones that let the shapes speak for themselves. Later, in Synthetic Cubism, color returned-but it was flat, bold, and used like a design element, not to mimic reality.

Did Cubism influence modern design?

Absolutely. The Bauhaus movement, Swiss graphic design, and even Apple’s minimalist interfaces owe something to Cubism. The idea of reducing objects to essential shapes? That’s Cubist. The use of overlapping planes in web design? That’s Cubist. Modern logos often use fragmented, multi-angle forms because they communicate complexity without clutter.

Was Cubism only a painting movement?

No. Sculpture, collage, typography, and even poetry were transformed by Cubism. Artists like Alexander Archipenko and Raymond Duchamp-Villon created three-dimensional Cubist sculptures. Poets like Guillaume Apollinaire wrote "Cubist poems"-lines broken into fragments, rearranged like visual shapes. It was a full cultural shift, not just an art style.

Why did Cubism decline after 1914?

World War I changed everything. Braque was drafted and nearly killed in 1915. Picasso moved toward a more classical style. The radical energy of Cubism couldn’t survive the war’s trauma. But its ideas lived on. By the 1920s, artists like Mondrian and Léger were turning Cubist geometry into pure abstraction. The revolution didn’t end-it spread.