Imagine a sculpture that doesn’t just sit still-it twirls, sways, and dances with the wind. That’s kinetic art. It’s not just about shape or color. It’s about movement. And that movement changes everything. Kinetic art isn’t new. People have been trying to capture motion in art for thousands of years. But it wasn’t until the 20th century that artists figured out how to make art actually move-without help from viewers, fans, or magic.

The First Sparks: Ancient Ideas, Modern Execution

Long before motors and magnets, ancient cultures played with motion in art. The Greeks built wind-driven wind chimes called aeolipiles-simple devices that rotated when air passed through them. In China, hanging metal bells and carved wooden figures moved with the breeze in temple courtyards. These weren’t called art back then. They were ritual objects, tools, or decorations. But they were kinetic. They proved that movement could be part of beauty.

It wasn’t until the 1920s that artists started treating motion as the main subject. Before that, painters tried to suggest motion-like Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase with its blurred figures. But those were illusions. Kinetic art didn’t pretend. It moved for real.

The Birth of Modern Kinetic Art

The real turning point came with Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner. In 1920, they wrote the Realistic Manifesto, declaring that art should embrace space and time. They didn’t carve stone or paint canvas. They built sculptures from glass, metal, and plastic that responded to air currents or motors. Gabo’s Linear Construction in Space No. 1 (1942-43) used nylon threads stretched between metal frames, creating shifting shadows and forms as you walked around it. It wasn’t static. It changed with your perspective.

Then came Alexander Calder. His mobiles-delicate, balanced structures of painted metal-hung from ceilings and drifted with the slightest draft. Calder didn’t use motors. He used physics. Gravity, balance, and air. His work made people stop and watch. You couldn’t just glance at a Calder mobile. You had to sit with it. Watch how it settled, how it stirred, how it found new shapes. That’s when kinetic art stopped being a novelty and became an experience.

Post-War Innovation: Motors, Magnets, and Machines

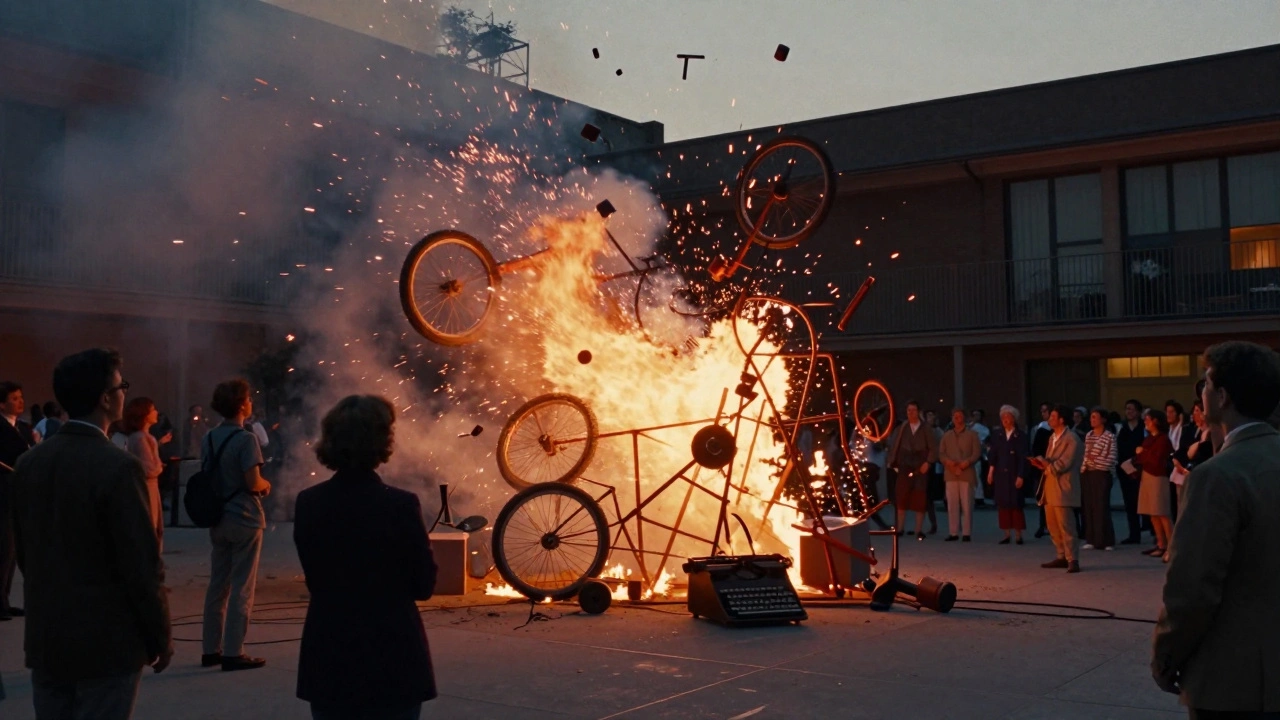

After World War II, technology exploded. Artists didn’t just use wind anymore. They used electricity. Motors. Solenoids. Light sensors. In the 1950s and 60s, artists like Jean Tinguely turned machines into art. His Homage to New York (1960) was a giant, self-destructing sculpture made of scrap metal, bicycle wheels, and a typewriter. It played music, smoked, and eventually caught fire in the MoMA courtyard. It was chaos. It was art. And it was alive.

Meanwhile, in Europe, artists like Group Zero-led by Otto Piene and Heinz Mack-used light and movement to create immersive environments. Piene’s Light Ballet used rotating projectors to cast moving patterns on walls. Viewers didn’t just look at the art-they stepped inside it. The line between observer and participant began to blur.

Kinetic Art in the Digital Age

Today, kinetic art doesn’t need physical parts to move. Digital screens, sensors, and code have opened new doors. Artists like Rafael Lozano-Hemmer use motion capture to turn people’s movements into light trails on building facades. In Melbourne, the Light Up Melbourne festival features projections that respond to crowd density-brighter when more people gather, dimmer when the square empties.

Even traditional kinetic artists are blending old and new. Take Anthony McCall’s Line Describing a Cone (2004). A beam of light rotates slowly in a dark room, and viewers stand in its path. Their bodies become part of the sculpture. The art moves, yes-but so do you. The experience is shared. The motion is collective.

Why Kinetic Art Matters

Static art tells you a story. Kinetic art pulls you into it. It doesn’t wait for you to come close. It reaches out. It breathes. It reacts. That’s why it feels alive.

It challenges the idea that art must be permanent. A Calder mobile can be taken down, stored, and rehung. It’s not ruined by time-it’s renewed by motion. It’s not about preserving a moment. It’s about inviting change.

And in a world that moves faster every year, kinetic art mirrors our reality. We scroll. We swipe. We stream. We never stay still. Kinetic art doesn’t fight that. It embraces it. It turns motion from distraction into meaning.

What Makes Kinetic Art Different

Not all moving art is kinetic. A spinning ceiling fan isn’t art. A wind chime on a porch isn’t art-unless it’s designed to make you pause, to make you wonder how it works, to make you feel something as it turns.

Kinetic art requires intention. Every gear, every wire, every balance point is chosen. It’s not random. It’s choreographed. Even when it looks chaotic, like Tinguely’s machines, there’s a hidden rhythm. The artist controls the variables-speed, weight, direction-so the movement feels purposeful.

Compare that to a child’s pinwheel. It spins. It’s pretty. But it doesn’t ask questions. Kinetic art does. Why does it move this way? What happens if the wind stops? Does it need power-or can it live on air alone?

Where to See Kinetic Art Today

You don’t need to travel to a museum to find it. Public spaces are full of it. In Singapore, the Marina Bay Sands has a kinetic sculpture called Hydroponic Garden-a tower of hanging metal leaves that ripple with the wind. In Berlin, the Wind Sculpture VII by Yinka Shonibare spins in the park, its fabric patterns catching the light like a kaleidoscope.

In Melbourne, the National Gallery of Victoria often features rotating kinetic installations. One recent exhibit used magnetic fields to make steel balls float and roll across glass surfaces, leaving trails of light. Visitors lined up to watch them-some for over twenty minutes. No sound. No explanation. Just movement.

Even commercial spaces use kinetic art. Apple Stores now have custom-designed hanging installations that sway gently with the building’s airflow. They’re subtle. They’re quiet. But they make the space feel alive.

The Future of Motion in Art

Artists are now working with AI to create kinetic pieces that learn from their environment. A sculpture might change its rhythm based on weather data, traffic noise, or even the emotional tone of social media feeds. Imagine a piece that slows down during a rainstorm or speeds up when the city buzzes with energy.

Some are even exploring bio-kinetic art-using living organisms. A project in Tokyo uses algae that glow when stirred by gentle currents. The movement isn’t mechanical. It’s biological. The art breathes.

What’s clear is this: kinetic art isn’t fading. It’s evolving. And it’s becoming more personal. It’s no longer just about the artist’s idea. It’s about how you move through the world-and how the world moves around you.

What You Can Do With Kinetic Art

You don’t need a degree in engineering to make kinetic art. Start small. Hang a metal spoon from a string. Add a small magnet. Place another magnet beneath it. Watch how it swings, how it resists, how it finds a rhythm. That’s kinetic art. It’s physics. It’s patience. It’s wonder.

Or try a smartphone app that turns your camera into a motion sensor. Point it at a tree. Let the wind move the leaves. Capture the motion. Turn it into a looping video. Now you’ve made kinetic art. No motors. No wires. Just observation.

Kinetic art doesn’t ask for perfection. It asks for attention. If you notice the way a curtain flutters in the breeze, you’re already seeing it. The next step? Let it inspire you to make something that moves-and makes someone else stop to watch.